Nike's CEO Buying Stock Matters More Than Most People Think

Plus... the one thing you'll never find on a spreadsheet

Like most stories I write about, I can’t stop thinking about this.

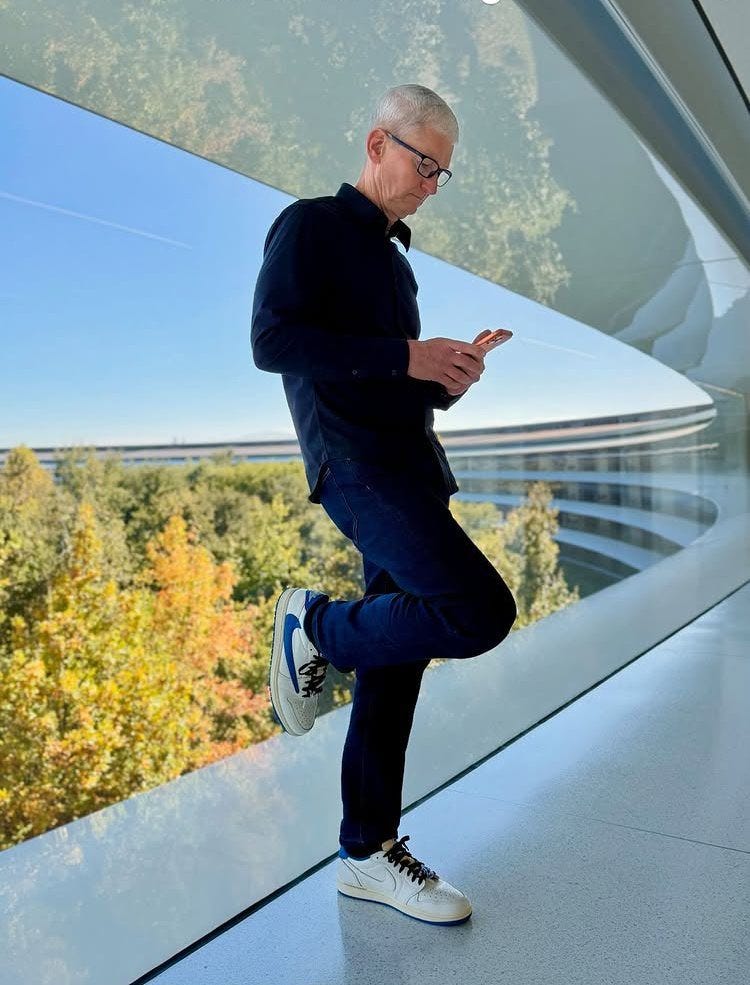

Matthew Kish reported Friday that Nike CEO Elliott Hill bought stock. Apple CEO Tim Cook, a longtime Nike board member, nearly doubled his stake in the company on December 22, purchasing roughly $3 million in shares. Former Intel CEO Bob Swan, also a Nike board member, purchased $500,000 in shares the same day.

And I keep coming back to it... because this feels different than the usual corporate theater we’re subjected to.

This is the opposite of the smoke and mirrors we see with licensing conglomerates like Authentic Brands Group’s recent moves. This is the transparency I believe we’re going to see more of in 2026... or at least, the transparency we desperately need.

Put your money where your mouth is.

When CEOs buy their own stock during rough stretches, it means something different than talking about “long-term vision” while selling shares or taking guaranteed bonuses. Hill bought Nike stock as it dropped 19% in 2025. Cook, already a board member, chose to nearly double his Nike position. Swan added half a million. That’s not a press release. That’s belief. That’s skin in the game.

And maybe that’s why I can’t stop thinking about it.

The Signal vs. The Noise

Here’s what we’re used to... executives talking about confidence while their compensation packages are structured to pay out whether the company succeeds or fails. Stock options that vest regardless. Golden parachutes that reward failure. Severance packages that make layoffs profitable for leadership.

We’re used to CEOs who show up, make cuts, optimize for quarterly earnings, then leave with tens of millions before the long-term consequences hit.

Hill buying Nike stock in December 2025, after a brutal year where shares fell nearly 20%, sends a different message. He’s betting his own money that the decisions he’s making will work. Not stock options granted as part of a compensation package. Not restricted stock units that vest automatically. His money. His choice. His belief.

Cook doing the same... not just as Apple’s CEO watching from the sidelines, but as a Nike board member with insider knowledge of the company’s challenges and turnaround plans. He’s doubling down. Swan, who led Intel through its own transformation challenges, is putting in half a million.

The signal is clear: “I believe in what we’re building enough to risk more of my own wealth on it.”

The Multi-Layered Ownership Problem

I wrote recently about Reebok’s approach under Authentic Brands Group... smart glasses partnerships, fragrance deals, licensing plays that look good in press releases but don’t actually build brand value. But I need to be precise here... ABG isn’t traditional private equity. They’re something potentially worse: a licensing conglomerate that treats iconic brands like intellectual property portfolios to be monetized rather than businesses to be built.

And they’re expanding. ABG just announced a deal with Kevin Hart to manage his name and likeness rights. They own Reebok, Brooks Brothers, Sports Illustrated, Forever 21, and dozens of other brands. Their model: acquire struggling brands, strip away operational complexity, license the name to whoever will pay, repeat.

But ABG is just one example of a broader problem... multi-layered ownership structures that obscure accountability and optimize for asset extraction rather than brand building. Let’s look at the landscape:

Licensing Conglomerates (like Authentic Brands Group, Iconix Brand Group, Sequential Brands)

Acquire brands primarily for IP value

License everything: products, retail, geographic territories

Minimal operational involvement

Success measured by licensing revenue, not brand health

Examples: ABG’s Reebok, Champion, Prince tennis; Iconix’s Starter, Umbro, Candie’s; Sequential’s formerly owned Jessica Simpson, And1

Private Equity Firms (like Sycamore Partners, Permira, Advent International)

Buy companies to optimize and flip within 3-7 years

Focus on cost reduction and EBITDA improvement

Extract value through leveraged buyouts

Success measured by exit multiples, not long-term sustainability

Examples: Sycamore’s Talbots, Belk, Hot Topic; Permira’s formerly owned Golden Goose; Advent’s Lululemon (2005-2007)

Holding Companies (like VF Corporation, Tapestry, Capri Holdings)

Long-term ownership with operational oversight

Multiple businesses under one corporate umbrella

Success measured by portfolio performance

Can be good or bad depending on management philosophy

Examples: VF Corp’s Vans, The North Face, Timberland; Tapestry’s Coach, Kate Spade; Capri’s Versace, Jimmy Choo, Michael Kors

Investment Groups/Consortiums (like Anta Sports, Fosun International, CVC Capital Partners)

Often strategically motivated acquisitions

May lack operational expertise in the specific industry

Accountability diffused across multiple stakeholders

Examples: Anta’s Fila China, Amer Sports (Arc’teryx, Salomon, Wilson); Fosun’s Wolford, St. John; CVC’s Breitling (relevant for luxury brand management)

I experienced this firsthand when Farfetch collapsed. I lost equity I’d been promised when the company went through complex ownership changes and restructuring. The people making decisions about my compensation were layers removed from the actual work, from the promises made, from the human cost of those financial maneuvers. That’s what multi-layered ownership does... it creates distance between decisions and consequences.

What these structures share: the people making decisions often aren’t investing their own capital in the outcome. They’re managing other people’s money, optimizing for their investors’ timelines, not the brand’s legacy.

ABG’s recent Kevin Hart deal illustrates the problem perfectly. They’re not building Hart’s brand in any meaningful way... they’re monetizing his name through licensing deals. Slap “Kevin Hart” on products, collect fees, repeat. It’s the same approach they’re taking with Reebok: maximize short-term licensing revenue while the brand equity accumulated over decades slowly depletes. Again, I hope I am wrong but…

You know what executives at licensing conglomerates, private equity firms, and multi-layered ownership structures don’t do? Buy more equity in the brands they’re managing.

Because they know the game. They’re optimizing for the exit, the licensing fee, the next quarterly distribution to investors... not the outcome. They’re building a story to sell, not a company to sustain.

When you see ABG-owned brands announcing partnerships or “strategic initiatives,” ask yourself: would the people making these decisions invest their own money in the result? Or are they just maximizing licensing revenue before moving to the next acquisition?

The difference between Hill buying Nike stock and these complex ownership structures is the difference between building and extracting. One requires belief. The other just requires a financial model.

What Transparency Actually Looks Like

I’ve been writing about transparency as the defining trend for 2026... the shift away from nostalgia-as-business-strategy toward actually building things people want.

CEO stock purchases are transparency in its purest form. It’s putting a number on belief. It’s making the internal conviction external and verifiable.

When Elliott Hill bought stock, he didn’t issue a memo about “having confidence in Nike’s trajectory.” He demonstrated it. When Tim Cook bought Apple shares, he didn’t schedule an all-hands meeting about “believing in our future.” He showed it.

This matters because we’ve been drowning in corporate speak for so long that we’ve forgotten what actual commitment looks like.

“We’re committed to innovation.” Cool, show me the R&D budget and the product pipeline.

“We believe in our people.” Great, show me retention rates and internal promotion data.

“We’re confident in our long-term strategy.” Fantastic, show me leadership buying stock instead of selling it.

Words are free. Buying your own company’s stock during a down year? That costs something.

Why This Matters for Company Culture

Here’s what I’ve learned over the last 20+ years of working in footwear-related businesses, watching a startup grow from nine people to a global platform, and being a disposed piece in the acquisition game puzzle…

The people inside a company know when leadership actually believes versus when they’re just performing belief.

Employees see everything. They see who’s selling stock at the first opportunity. They see who’s optimizing their comp package for a quick exit. They see who shows up every day to do the work. They see who’s genuinely invested in building something that lasts.

When a CEO buys stock during a tough year, everyone in that company knows. And it changes the calculation for whether to stay, whether to push harder, whether to believe the turnaround story leadership is telling.

It’s the difference between “trust me” and “I’m all in with you.”

I wrote about Nike’s relentless layoff cycles and how they destroyed institutional knowledge... how constant restructuring optimized for short-term cost savings while gutting the expertise that made Nike successful in the first place. That’s what happens when leadership is incentivized to hit quartrly targets, not build decade-long success.

CEO stock purchases can’t undo that damage. But they signal a different kind of thinking. They signal: “I’m here for what this becomes, not just what it does this quarter.”

And for employees who’ve survived multiple rounds of cuts, who’ve watched talented colleagues disappear while being told “trust the process”... seeing leadership invest their own money in that process means something.

The Accountability Test

Take away all the small talk and this is about one thing: accountability.

When you buy your own company’s stock, you’re accountable for the results in the same way your employees and shareholders are. You win when they win. You lose when they lose.

That’s different than:

Compensation packages that pay out regardless of performance

Stock options granted at discounted prices with guaranteed vesting

Severance agreements that reward failure

Consulting deals that kick in after departure

Those structures create asymmetric risk... leadership gets paid either way, so the incentive is to optimize for personal outcomes, not company outcomes.

Buying stock aligns those incentives. Suddenly, the decisions that hurt long-term value also hurt you personally. The cost-cutting that boosts this quarter’s numbers but destroys next year’s capability? That’s your money you’re burning, too.

This is why executives at licensing conglomerates and private equity firms don’t do this. They’re not accountable for long-term outcomes. They’re accountable to their investors’ exit timelines or their licensing revenue targets. The incentives are misaligned by design.

In my experience, those layers... they add a lack of care in both directions. For team members who aren’t in the room for conversations they would have been in otherwise, there’s fear of the unknown. For leadership, those same layers bury accountability for the human aspects of running a business.

Someone from three levels and two companies removed from a situation doesn’t think about the human element of firing someone, laying someone off, or cutting a budget. They’re just looking at numbers on a spreadsheet. And I may not be a data scientist, but I can guarantee there is one thing you will never find on a spreadsheet: empathy.

That distance makes it easy to make decisions that look rational on paper but destroy lives, careers, institutional knowledge, and ultimately... the company itself.

When a CEO buys stock in their own company, those layers collapse. The distance disappears. Your decisions affect real people... including you.

What This Signals About 2026

I believe we’re entering an era where people are tired of being sold stories. They want to see proof.

Customers want products that actually work, not marketing campaigns about innovation

Employees want leadership that believes in the mission, not executives optimizing for their next role

Investors want sustainable growth, not financial engineering

Communities want companies that contribute, not extract value and leave

CEO stock purchases are a small signal of a larger shift... toward transparency, toward alignment, toward actually building instead of just positioning.

When Hill bought Nike stock, he made a bet that his turnaround plan will work. Not in press releases. Not in strategy decks. In dollars.

When Cook nearly doubled his Nike stake, he demonstrated belief in the company's direction. Not as an outside observer, but as a board member with full visibility into the challenges and the turnaround strategy.

These actions create accountability. They force alignment. They make the long-term success of the company directly tied to the personal financial outcomes of the people making the decisions.

That’s how it should work. That’s what we need more of.

The Compensation Context

Here’s where this gets interesting... and where we need to be honest about the full picture.

Elliott Hill’s compensation package when he returned to Nike in October 2024 included significant stock-based incentives. According to Nike’s SEC filings, Hill received a base salary of $1.5 million, but the real value came from equity: $28 million in restricted stock units and performance-based stock awards that vest over multiple years based on Nike’s performance.

So when Hill bought additional Nike stock in December 2025, he was already heavily invested through his compensation package. The SEC Form 4 filing shows he purchased shares on the open market, separate from his granted equity.

This is important context. Hill isn’t some outside observer betting on Nike... he’s already structurally tied to the company’s performance through his comp package. His wealth is already linked to Nike’s stock price through those RSUs and performance awards.

But here’s why the additional purchase still matters: those granted shares were part of his employment agreement. They were negotiated. They were expected. Buying more shares with his own money, after watching the stock fall 19%, is different.

It’s the difference between “my contract requires me to hold this stock” and “I’m choosing to increase my position during a downturn.”

Think about it this way... if Hill believed Nike’s turnaround was going to fail, he could have:

Sold existing shares he already owned (within legal trading windows)

Simply held what he was granted without adding more

Structured his comp package differently to include more cash, less equity

Instead, he bought more. After a brutal year. With his own capital.

That’s the signal. Not that he has equity (every CEO does), but that he’s voluntarily increasing his exposure when he could have done the opposite.

Compare this to executives who:

Max out stock sales at every trading window

Exercise options and immediately sell

Negotiate comp packages heavy on cash, light on equity

Structure deals to minimize their downside risk

Hill’s doing the opposite. His comp package already tied him to Nike’s performance. Then he chose to tie himself even more.

According to Nike’s proxy statement filed with the SEC, Hill’s total target compensation for his first year back was approximately $29.5 million, with about 95% of it performance-based and delivered in equity rather than cash. Then he went out and bought more stock on top of that.

Some might argue this is just optics... a CEO with a $30 million comp package buying a few hundred thousand in stock is meaningless. Maybe. But it’s also unnecessary. He could have just pointed to his existing equity stake and said, “I’m already all in.”

The fact that he chose to buy more, publicly, during a down year, sends a message beyond just the dollar amount. It says: “Even knowing everything I know from inside the company, I’m betting more of my wealth on this working.”

That’s different than just collecting granted equity. That’s active belief.

The Signal to the People Who Actually Wear the Shoes

Here’s something that doesn’t get talked about enough in business coverage: Elliott Hill buying Nike stock isn’t just a signal to Wall Street analysts. It’s a signal to the people who actually wear Nike every single day.

I know dozens of people who own a minimal amount of Nike stock... maybe 10 shares, maybe 50, some even more. They all bought because they love the brand, not because they’re building a diversified portfolio. These aren’t day traders. They’re sneakerheads who wanted to feel more connected to the company. They wear Nike proudly day in and day out. They follow every product launch. They care about where the brand is headed in a way that goes beyond quarterly earnings.

That’s different than most companies on the stock market. People don’t have that emotional connection to their holdings in Procter & Gamble or Johnson & Johnson. They might use those products, but they don’t identify with them. They don’t wear the logo as a statement about who they are.

Nike is different. So is Apple. Maybe a handful of other brands. When you wear a Swoosh, you’re making a choice about your identity. When you buy Nike stock, even just a few shares, you’re investing in something you believe represents excellence, innovation, achievement.

When Elliott Hill buys stock during a down year, those fans feel seen. They feel validated. “The CEO believes in this as much as I do. We’re in this together.”

That might sound sentimental, but it matters. Because those core fans... the ones who own a few shares and wear the gear and defend the brand in arguments with their Adidas-loving friends... they’re the foundation. They’re the word-of-mouth marketing that money can’t buy. They’re the cultural ambassadors who keep Nike relevant even when the quarterly numbers look rough.

Will Hill buying stock solve Nike’s problem of appealing to younger consumers who are choosing On or Hoka? No. Will it fix the overproduction issues or the wholesale relationship damage? No. Will it magically restore the institutional knowledge that got gutted through constant layoffs? No.

But it does something that’s harder to quantify... it reminds the core audience that leadership cares about the same thing they care about. Not just the stock price, but what Nike represents. The belief that the brand still stands for something beyond quarterly earnings.

When fans see the CEO buying more stock during a tough year, it reinforces their own decision to stay loyal. “He’s not bailing. Neither am I.”

That’s more valuable than it gets credit for. Because brand loyalty isn’t built through marketing campaigns or limited releases. It’s built through shared belief. And when leadership demonstrates that belief publicly, with their own money, during challenging times... it strengthens the bond with the people who’ve been believers all along.

Wall Street might see Hill’s stock purchase as a positive signal about Nike’s turnaround prospects. The sneakerheads who own 25 shares see something different: proof that the person running the company actually gives a shit about more than just the exit strategy.

Both signals matter. But in an industry built on culture and identity and connection... the second one might matter more.

The Broader Pattern

This isn’t just about Nike or Apple. It’s about what leadership actually looks like when stripped of corporate theater.

Real leadership requires belief. Real belief requires risk. Real risk requires putting something of yours on the line.

For too long, we’ve accepted a model where executives got rich regardless of outcomes, where leadership could talk about “skin in the game” while structuring deals that protected them from downside risk, where “betting on yourself” meant negotiating a better exit package.

Maybe 2026 is when we stop accepting that. Maybe the companies that win are the ones where leadership is genuinely invested... not just in their own compensation, but in the actual long-term success of what they’re building.

Maybe transparency stops being a buzzword and starts being a requirement.

Maybe we start asking: if you believe in this strategy, why aren’t you buying stock?

What This Means for Nike Specifically

Elliott Hill returned to Nike in October 2024 after John Donahoe’s tenure left the company struggling. Sales down. Market share lost to Hoka and On. The wholesale relationships severed. The DTC strategy that didn’t work as planned.

Hill’s a 32-year Nike veteran. He started as an intern in 1988. He understands what made Nike work before the cost-cutting and restructuring cycles gutted institutional knowledge. He’s seen the company at its best.

And now he’s betting his own money that he can get it back there.

That’s not a small thing. Nike’s stock fell 19% in 2025. That’s not a “buy the dip” trade. That’s a statement: “I believe in what we’re building enough to risk my wealth on it.”

Will it work? I don’t know. But I know the alternative... CEOs who cut costs, boost short-term metrics, cash out, and leave before the consequences hit... has failed Nike repeatedly.

At minimum, Hill’s stock purchase signals he’s playing a different game. He’s accountable for the long-term outcome, not just the next quarterly report.

For a company that’s been destroyed by short-term thinking, that alone is progress.

The Question for Other CEOs

Here’s the test I want to see more companies face: if you believe in your strategy, why aren’t you buying stock?

If you’re cutting workforce to “operate more efficiently,” are you betting your own money that those cuts will lead to better outcomes?

If you’re pursuing new initiatives, new partnerships, new “strategic directions,” are you personally invested in whether they work?

If you’re asking employees to trust the turnaround plan, are you demonstrating that trust with your own capital?

Because if the answer is no... if you’re talking about confidence while structuring your comp to pay out regardless... then maybe the strategy isn’t as solid as you’re claiming.

Actions over announcements. Skin in the game over spin.

Put your money where your mouth is.

Why I Keep Coming Back to This

I said at the beginning that I can’t stop thinking about this story. Here’s why.

For 20 years, I’ve watched the sneaker industry operate on hype, on stories, on the promise of what’s coming next. I’ve watched brands talk about innovation while reissuing the same silhouettes. I’ve watched executives talk about believing in their people while running constant layoff cycles. I’ve watched companies talk about long-term vision while optimizing every decision for short-term metrics.

And I’ve watched it fail. Over and over.

Under Armour’s failure with Steph Curry? That’s what happens when leadership doesn’t truly believe in the cultural side of the business, when they’re focused on quarterly performance over building something lasting.

Nike’s struggles under Donahoe? That’s what happens when an outsider CEO optimizes for digital transformation metrics without understanding what made the company special in the first place.

The endless parade of signature shoes that don’t connect culturally? That’s what happens when brands are chasing short-term revenue, not building long-term legacies.

CEOs buying their own stock during rough years represents the opposite of all that. It represents belief. Commitment. Accountability. The long view.

Maybe that’s why I can’t stop thinking about it. Because it’s so rare that when it happens, it stands out.

And maybe if more CEOs operated this way... if more leadership was genuinely invested in long-term outcomes, not just their own comp packages... we’d see fewer catastrophic failures driven by short-term optimization.

The Transparency Trend Continues

This connects to what I’ve been writing about... the shift away from nostalgia-as-business-strategy toward actually building valuable things. The move away from hype cycles toward substance. The rejection of corporate theater in favor of authentic action.

CEO stock purchases are a piece of that puzzle. They’re proof, not promise. They’re verification, not vapor.

When Hill bought Nike stock in December 2025, he didn’t post about it on LinkedIn with a heartfelt message about believing in the team. He just did it. The SEC filing came out. The signal was sent.

That’s transparency. Not the performed kind, where companies issue statements about their values. The real kind, where actions are public and verifiable and costly.

I think we’re going to see more of this in 2026. Not because executives are suddenly more ethical, but because the audience... customers, employees, investors... is done with smoke and mirrors. They want proof. They want alignment. They want leadership that’s accountable for outcomes, not just quarterly performance.

CEO stock purchases won’t fix every problem. They won’t undo years of bad decisions or restore lost institutional knowledge or magically create great products.

But they signal a different kind of leadership. One that’s willing to risk something. One that’s accountable for what comes next.

And in an industry that’s been dominated by executives who talk about taking risks while structuring deals to eliminate their own downside... that’s meaningful.

What Comes Next

I’ll be watching to see if this becomes a trend. If more CEOs start putting their money where their strategies are. If boards start demanding this kind of alignment instead of just approving massive comp packages.

I’ll be watching to see if Hill’s bet on Nike pays off. If his turnaround strategy works. If institutional knowledge can be rebuilt after being systematically destroyed.

And I’ll be watching to see if the broader shift toward transparency continues... if companies start being judged by actions rather than announcements, by results rather than press releases, by whether leadership is genuinely invested in building something that lasts.

Because if 2026 is the year when talk becomes cheap and action becomes the currency that matters... that’s the shift the entire industry needs.

Put your money where your mouth is.

That’s the standard. That’s the test. That’s what leadership should look like.

Let’s see who meets it.

I’m Nick Engvall, and I’ve been writing about sneakers and culture for nearly two decades, from building Eastbay’s first blog to being employee #9 at StockX. I run Sneaker History (website and podcast) and write The Sneaker Newsletter... the stories that connect what we wear to who we are. I want to believe CEOs buying stock actually changes things. Ask me again in a year if it did.