How Sneaker Brands Lose the Plot

When your ownership structure needs a flow chart, where is your soul?

I fell in love with Reebok on March 12th, 1997.

That’s the night Allen Iverson crossed over Michael Jordan at the First Union Center in Philadelphia. AI was wearing the Question Mid... white and blue, that distinctive hexalite sole, Reebok’s vector logo on the side. He wasn’t just wearing them. He was making a statement… I’m different, and that’s exactly the point.

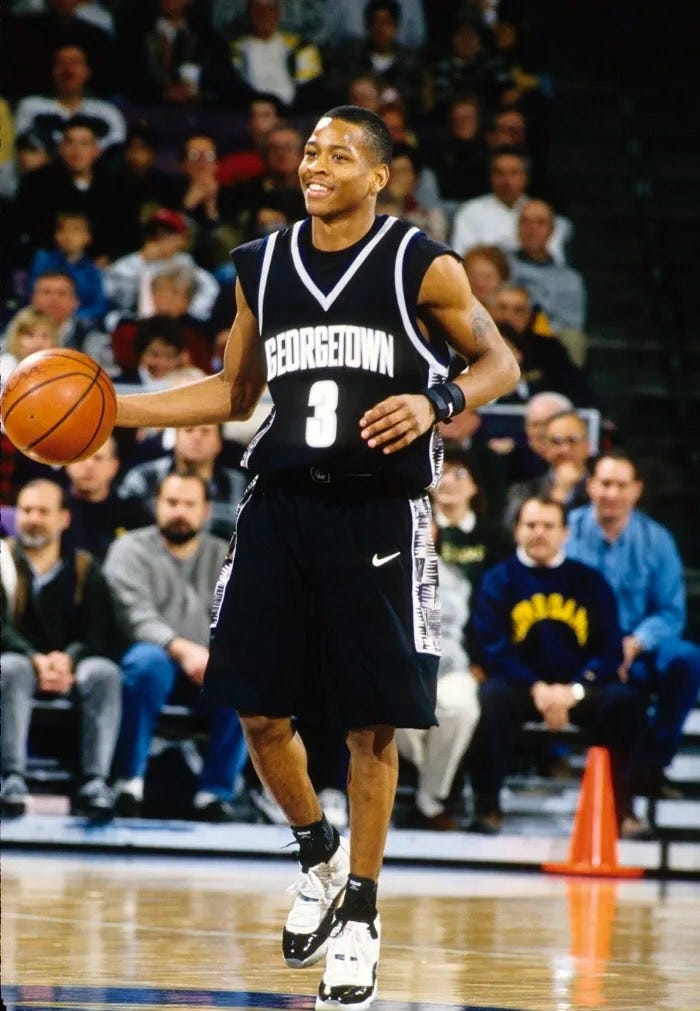

But my love for Allen Iverson started years earlier.

Summer of 1992, visiting my uncle and his family in the DC area. I was a kid who knew college wasn’t in the cards for me, but I spent hours fantasizing about going to Georgetown, North Carolina, or UNLV. Places where basketball mattered. Where the shoes mattered.

A couple years later, Allen Iverson shows up at Georgetown wearing some of the most classic Nikes and Jordans the Hoyas ever had. The Air Up. The Air Way Up. The Air Strong. And those Air Jordan 11 Concords that became legendary. I’ve written about AI’s entire sneaker journey... every shoe from Georgetown through his final NBA seasons... because nobody influenced how I thought about basketball and identity more than him.

So when Iverson signed with Reebok in 1996, leaving Nike behind, I paid attention. Nike wanted him but couldn’t promise he’d be the guy. Reebok said “you can be yourself here.” Cornrows, tattoos, hip-hop... all the things the NBA wanted to sanitize, Reebok embraced. That wasn’t a marketing strategy. That was authenticity.

I’ve been rooting for Reebok ever since. Through the Pump Up and Air Out commercials that actually competed with Nike. Through Iverson’s MVP season. The Jadakiss commercials. Through the S. Carter collection when Jay-Z basically made Gucci Tennis shoes and Reebok said “yeah, let’s do it.” Even when I was at Finish Line and we partnered with Reebok and Kendrick Lamar to relaunch the Classic... I believed in what the brand could be. Hell, we even tried to partner with Reebok at Stadium Goods when I was there—a story for another day.

But something’s been broken for a while now. And this week, I think I might have figured out exactly what it is.

On February 19th, 2025, Reebok issued a press release announcing new ownership structures. Not the ownership... just pieces of it. Galaxy Universal acquiring global product creation and sourcing. A joint venture for European operations. Licensing agreements. Manufacturing partnerships.

This has stuck in my head… I had to read that sentence three times to understand who actually owns what.

And if I’m confused... someone who’s worked at Sole Collector, Complex, StockX, Finish Line, and Stadium Goods for 20 years... what chance does a 16-year-old sneakerhead have?

More importantly, when your press release reads like a corporate ownership flowchart, where’s the room for the rebellious energy that made Allen Iverson sign with you in the first place?

Every company listed in that press release needs to make money. That’s not controversial... that’s capitalism. But here’s what happens when you stack that many entities between “we have a great idea” and “let’s make it happen”:

Layer 1: Authentic Brand AB (Reebok’s owner since 2021) needs to see ROI on their investment, answers to their investors, and cares more about quarterly reports than quarterly shoes.

Layer 2: Galaxy Universal (product creation & sourcing) focuses on manufacturing margins, minimum order quantities, and production timelines that prioritize efficiency over creativity.

Layer 3: Various licensing partners (US footwear, European ops, etc.) collect licensing fees, run approval processes, and make risk-averse decisions because they didn’t buy the brand, they rented it.

Layer 4: Retail partners need product that moves fast, want safe bets not risks, and prefer proven formulas over experimentation.

By the time an idea makes it through all those layers, what’s left? A shoe. Maybe a decent shoe. But not a Reebok shoe in the way that the Question or the Pump Fury or even the Answer IV were Reebok shoes.

Here’s where it gets absurd…

When you’re a private equity-owned brand portfolio, every property becomes an opportunity for licensing revenue. And when licensing revenue is the goal, brand coherence becomes optional.

Reebok is now making smart glasses. Not performance eyewear for athletes. Smart eyewear. Bluetooth audio, hands-free calling, AI integration.

Is there a market for that? Maybe. Does it make sense for a tech company to pursue? Absolutely. Does it make sense for Reebok... a brand that should be laser-focused on reclaiming its position in basketball and fitness footwear... to dilute its identity with tech accessories?

Only if you’re thinking about Reebok as a logo to license rather than a brand to build.

And Reebok’s not alone. Authentic Brands Group also owns Champion. You know, the legendary sportswear brand that outfitted everyone throughout the 1980s and 1990s.

Champion is now making fragrances. Through a licensing deal with Revlon. Because apparently when people think “Champion,” they think “I need a new cologne.”

This is what happens when brands become portfolios. Every property is a potential revenue stream. Every logo is an opportunity to license to someone willing to pay fees.

What gets lost is… focus.

Nike doesn’t make cologne. They make shoes and apparel, and they’re religious about it. When you see the Swoosh, you know exactly what it means. When you see Reebok on smart glasses or Champion on a fragrance bottle, what does the logo even mean anymore?

And then there’s this: Authentic Brands Group partnered with Reshop to offer instant refunds.

On the surface, that sounds customer-friendly. Instant refunds! Great experience!

But let’s read between the lines. You don’t need a third-party returns management platform unless you have a lot of returns. And you don’t have a lot of returns unless either your product quality is inconsistent, your sizing is a mess, your marketing is overpromising and underdelivering, or all of the above.

This is what happens when you license manufacturing to the lowest bidder, approve designs by committee, and let marketing teams make promises your product can’t keep. Returns become so operationally burdensome that you need to outsource the entire problem to a specialist company.

That’s not a customer experience innovation. That’s a symptom of broken operations.